Of Cows and Other Creatures

Hommage To My Grandfather

Ernst, my paternal grandfather, was a simple hill farmer in Switzerland. He lived his entire life in a small village in the Emmental. The only chance for him to leave his town came during WWII when the war was playing out at the doorsteps of his country. For many weeks, Ernst was stationed close to the Italian border in the rugged Bedretto Valley, one of Switzerland's most isolated and remote places. He and the other soldiers monitored the activities of Italian forces under the regime of madman Mussolini. Later in life, Ernst often spoke about the almost three years spent in the mountainous terrain among Italian-speaking Swiss.

My grandfather grew up with nine older brothers and sisters on a small farm in the green hills. His mother, Elisabeth, my great-grandmother, died during his birth at a young age. My grandfather was raised by his sisters, who dutifully tried to take on the roll of their mother. As Ernst got older and most of his siblings married and moved away, he and his brother hired Rosalie, a young woman, to take care of the household. Rosalie proved to be a great help but was also a good companion to Ernst during the long winter nights. My grandfather was barely twenty when they got married, and shortly afterward, Rosalie gave birth to my uncle.

Ernst owned a couple of Simmental cows with big horns and docile faces. He gave them pretty names and took great pride in them. He loved his cows as much as he loved his children. Next to the cows, the couple owned a brown, long-legged horse named "Fanni," a few pigs, chickens, a dog, and some cats. Two more sons followed.

My grandfather worked long hours, planting potatoes, wheat, and rye, maintaining an orchard, and cutting and baling hay for his livestock.

He was not a man of many words. Ernst was known in town as a good-hearted, hardworking man. He refrained from leaving his farm at night, often too tired to socialize. When he went out, it was for a family wedding, funeral, or end-of-the-harvest party. During most celebrations, Ernst would get up and sing little, sad ballads; his tongue loosened up by one or two glasses of wine.

He lived in a small world, but he witnessed tremendous changes during his lifetime. When the first car rattled through town, he and his classmates ran out of the schoolhouse to watch the automobile, ignoring the teacher's instruction to remain indoors.

Years later, my dad finally convinced my grandfather to have a telephone installed instead of relying on messages from his neighbors. I remember him refusing to answer the phone, so Rosalie had to take the call.

My grandfather was also courageous, especially on the day he saved my grand-aunt Frieda's life. Frieda was my grandmother Rosalie's unmarried sister. She was born with a mental disability; her intellectual development remained at a child's level. Naturally, she was taken into my grandparent's family without the prospect of finding a husband. Frieda peeled apples and potatoes, fed the chickens, helped in the fields, and tended to the woodburning stove in the kitchen. She wore long, dark skirts covered by a linen apron. Her brown hair was held up in a tiny bun.

One day, while cooking on the stove, an ember sprang up on her outfit, and flames ignited her skirt within seconds. Frieda panicked and screamed in fear. Luckily, my grandfather was not far away. Instinctively, he picked up Frieda, carried her to the water fountain by the cowshed, and dunked her in the ice-cold water. Apart from a huge shock and burned clothes, Frieda was alright.

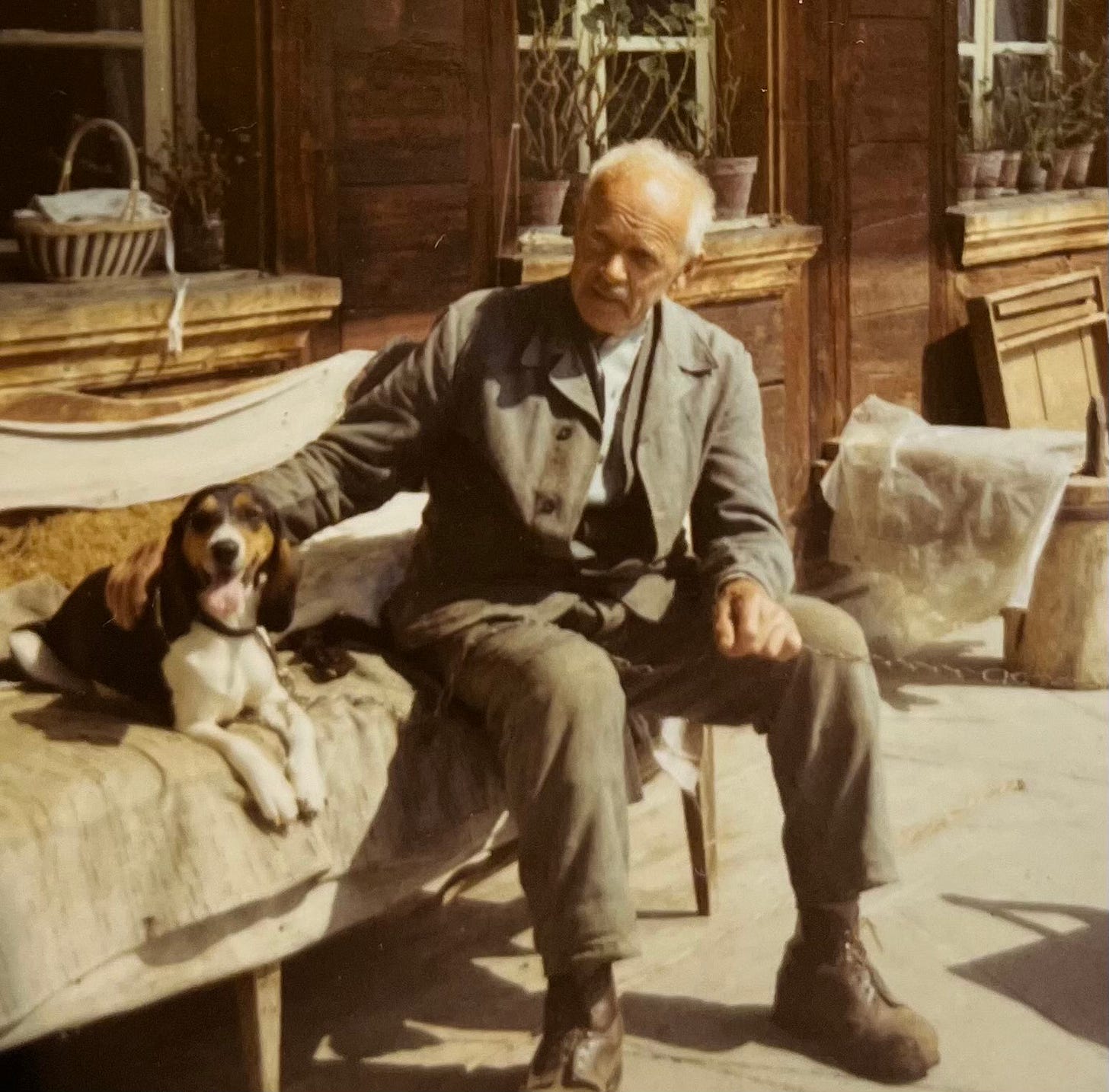

I remember my grandfather well. I remember the haircuts my grandmother Rosalie gave him on Sunday mornings on the sunny porch. I remember how he loved sitting on the wooden chair while she snipped around his head, enjoying his wife's attention. As a thank you, Rosalie always asked for a kiss.

I remember him eating his lunch while two cats sat on his shoulders, each trying to grab a bite off his fork. I remember helping him close the collar button on his Sunday shirt because his big hands could not handle the tiny fastener. I remember the sadness in his eyes when he had to bring one of his beloved cows to the butcher. I remember the tears on his cheeks as he told us what happened to "Bäri," his black dog, who was killed by a falling tree during log work in the snowy forest. But I also remember seeing the joy as he discovered a mother cat with her young kittens inside a kitchen drawer after she had given birth there overnight.

I don't remember Ernst being angry or unhappy. His life was mainly lived outdoors in nature with his animals and his family. My grandfather was not a wealthy man, and he did not own much. His farm and his family were his kingdoms.

Years later, at my wedding, my grandfather dressed his best in a traditional brown wool suit, the vest decorated with a shiny pocket watch, beaming with delight. Ernst, already in his eighties, needed a cane to walk. He was too old to sing his little, sweet ballads. But my grandfather and I managed one dance together; it was the most meaningful dance of the night. I was about to embark on a new life in America with a wonderful man on my side. Our lives parted in different directions; I only saw him once more before he died. I will never forget him.